1. Overview

Reports confirm that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic started in Wuhan (Hubei Province, China), where several cases of pneumonia patients were admitted in hospitals in December 2019 1,2. The COVID-19 virus was the etiological agent in the reported cases 1. The disease has been named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) 1,2. COVID-19 can be asymptomatic, or manifest as a mild to severe and fatal pneumonia 1,3,4. Its outbreaks caused a pandemic and COVID-19 has become a global threat with significant mortality and morbidity worldwide 1,2.

The COVID-19 virus is a member of the same group of ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) 1,5. The genome of the COVID-19 virus, named SARS‐CoV‐2, shares sequence identity with both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV 1,2.

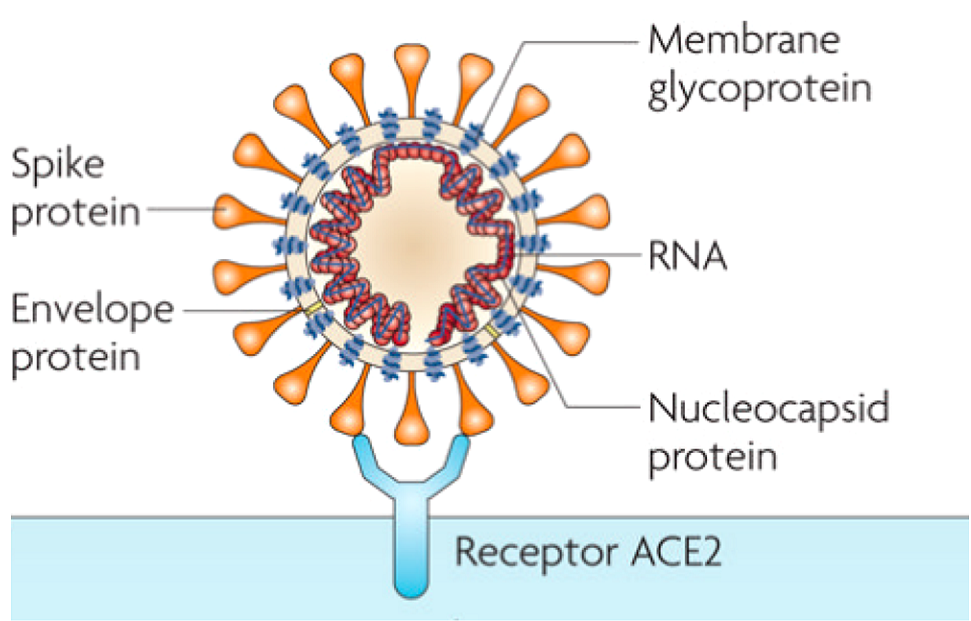

Human coronaviruses are common worldwide 5. Coronaviruses, members of Nidovirales order, are characterized as enveloped, non-segmented, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses, ranging from 60 nm to 140 nm in diameter and are named after their large surface spike proteins that look like a crown (corona) (fig.1) 5-7. They are host specific and can infect humans and animals alike 5,8. They are responsible for many diseases with various severity involving respiratory, enteric, hepatic, and neurological systems in humans and animals 2,6. Four distinct genera have been identified: alpha-, beta- gamma-, and deltacoronaviruses 5 . SARS and MERS are both caused by betacoronaviruses 5. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SARS‐CoV‐2 falls into the subgenus Sarbecovirus of the genus Betacoronavirus but is distinct from SARS‐CoV 2.

Many sources mention that the COVID-19 pandemic has a zoonotic origin from ‘wet markets’ in South China 1,5. Moreover, it was reported that the COVID-19 virus likely originated in bats, but the host reservoir is still unknown 2,7. Although environmental samples of the Huanan market in Wuhan were positive for the COVID-19 virus, no specific association with an animal has been confirmed as of yet 1. In addition, some of the positive patients did not visit the suspected market 1.

There is a large problem of asymmetry of risks and an irrational fear of a pandemic, coupled with media influence 10. Indeed, in 2003, the SARS killed a total of 774 and the bird flu around 100 people in 1997 10.

According to the daily report of the WHO, COVID-19 has resulted in 159 319 384 confirmed cases and 3 311 780 deaths by 12 May 2021, which translates into a mortality rate of approximately 2% 11,12 whereas the mortality rates of SARS and MERS were approximately 10% and 35% respectively 2,8. Moreover, there is much less concern over the seasonal flu that kills about 646,000 people worldwide each year 10.

2. Transmission, clinical features, and epidemiology

2.1. Transmission and clinical features

The transmission mode was reported to be human-to-human with close contact. The inhalation of infectious aerosols and droplets are the principal route of transmission of COVID-19, in addition to touching contaminated surfaces 1-3 7 and exchanging material such as money and phones .

Infected droplets can spread 1–2 m and deposit on surfaces 7. Studies mention that the virus remain viable on surfaces for days in favorable atmospheric conditions, but are destroyed in less than a minute by common disinfectants like sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide 7.

Based on clinical data of patients in the early phase of the COVID‐19 outbreak, the mean reproductive number (R0) was ranging from 2.20 to 3.58, which means that each patient spread the infection to two or three other people; but these numbers are not very accurate and more research is needed in the future 2,3.

The incubation period is reported to be ranging from 1 to 14 days, with a mean of 5 days and 95% of patients likely to experience symptoms within 12.5 days of contact 1-3. Non-specific symptoms include fever, cough, myalgia, headache and dyspnea with or without diarrhea1-4. The progression of infection leads to hypoxemia, difficulty in breathing and acute respiratory distress syndrome 1. Patients at this stage may require mechanical ventilation in intensive care units with quarantine facilities. Additionally, secondary bacterial infections may set in 1. Patients can be infectious as long as the symptoms persist 7.

2.2. Epidemiology

The rapid emergence and spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 around the world led to a large pandemic 13. Studies confirm that most of the reported case patients were aged between 30 and 79 years, with a mean age ranging from 49 to 59 years, including a few cases in children less than 15 years old 2-5.

In addition, more than 50% of the patients were male and almost half of the cases had coexisting medical conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases 2-4. People with these conditions, and the elderly are considered as high-risk for severe COVID-19. The case‐fatality rate was reported to be elevated among patients with coexisting medical conditions 2.

As cases can be asymptomatic, a confirmed case is defined as a suspect case with a positive molecular test 7. Real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) is routinely used as a primary diagnosis technique 2-4 7. Lower respiratory tract samples provide higher viral loads 2. The sampling operation may affect RT‐PCR testing results 2-4. Indeed, positive rates for throat swab samples were reported to be about 60% in early stage of COVID‐19, which means that the results obtained by RT-PCR should be interpreted with caution 2-4.

An interesting alternative that could be worth investigating is chest computed tomography (CT). Indeed, a study investigated the diagnostic value and consistency compared with the RT‐PCR test and found that the sensitivity of chest CT in suspected patients was 97% based on positive RT‐PCR results and 75% based on negative RT‐PCR results 2-4.

3. Therapeutic Options

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic an early 2020, one antiviral drug, remdesivir, was granted conditional marketing authorization by the EMA in July 2020 for the treatment of COVID-19 14. In the US, the antiviral drug remdesivir was approved in October 2020 by the FDA for use in a limited population, while the previously granted emergency use authorization of May 2020 was revised to permit use in other specified populations 15. Several other treatments were granted emergency use authorization by the FDA for the treatment of COVID-19 16. These treatments are mainly combinations of two drugs and include baricitinib and remdesivir, casirivimab and imdevimab, bamlanivimab and etesevimab, and COVID-19 convalescent plasma 17.

In most countries, treatment is essentially supportive and symptomatic 7. As a solution, some countries started pharmaceutical investigations but most of the countries were focused on non-pharmaceutical activities like lockdowns, social distancing, hygiene measures and closure of educational and recreational institutions, as well as 14 days of medical observation periods or quarantine for exposed and close contact persons 2,13. In addition, mild illness should be managed at home with counseling about danger signs as well as maintaining hydration and nutrition and controlling fever and cough 7.

A potential therapeutic option discussed by scientists is hydroxychloroquine. Traditionally, it is being used to treat malaria, but it is also a therapeutic option for several autoimmune diseases, especially systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis 18. In vitro studies showed antiviral properties of hydroxychloroquine making it interesting as a potential therapeutic option for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 18. However, clinical trials could not confirm its efficacy, in addition to raising concerns about its safety, especially in combination with other drugs 18.

Antiviral drugs, including oseltamivir, ribavirin, ganciclovir, lopinavir, and ritonavir were used to reduce viral load and prevent the likelihood of respiratory complications 2-4,7,19. Nevertheless, the efficacy of these antivirals needs to be verified overall by randomized and controlled clinical trials 2.

In addition to anti-virals, antibiotics and antifungals are also used mainly to prevent and control secondary microbial infections 2,7,19. Noninvasive or mechanical ventilation is applied to patients with hypoxia despite oxygen supplement and worsening shortness of breath 2,19. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is used as a last option 2,19.

Chinese herbal medicine are also used to prevent SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in 23 provinces in China 2,7,20. Indeed, using plants or plant extracts as well as microbial bioactive compounds could be future preventive and curative options for the management of COVID-19 by mainly acting as anti-virals and/or as boosters of the immune system.

4. Prevention

Since there is only one approved treatment for COVID-19 in a few countries and regions, prevention remains crucial 7,15. However, many researchers mention that COVID-19 is hard to prevent due to non-specific features of the disease such as its infectiousness even before the onset of symptoms during the incubation period, transmission from asymptomatic people, long incubation period, tropism for mucosal surfaces such as the conjunctiva, prolonged duration of the illness and transmission even after clinical recovery 7.

4.1. Recommended safety practices

According to the WHO, precautions need to be taken in order to minimize the infection risk. The actual hygiene preventive measures include washing hands regularly, use of sanitizers and wearing masks that have to be changed regularly. Depending on the composition of the masks, their role is to lower the spread of the virus 13 but not stopping it. One interesting invention in this case could be to create a face mask that inactivates the virus 13. At home, ventilation should be adequate with sunlight 7. Lockdowns, social distancing and quarantine for exposed and close contact persons are also recommended 2,13. The 3 Cs to be avoided are: spaces that are closed, crowded or involve close contact 21. Non-essential travel to places with ongoing transmissions should also be avoided. Cough hygiene should be practiced by coughing in your sleeves or a tissue rather than hands, and your hands should be regularly and thoroughly cleaned or washed straight away 7.

Concerning masks, the WHO recommends to clean hands before putting on a mask, as well as before and after taking it off, and after touching it at any time, and to ensure the mask covers your nose, mouth and chin 21. When taking off the mask, it should be stored in a clean plastic bag, and washed every day if it is a fabric mask, or disposed of in a trash bin if it is a medical mask 21. Use of masks with valves is not recommended 21.

In case of experiencing minor symptoms such as cough, headache, and a mild fever, the WHO recommends to stay home and self-isolate until recovery. When the symptoms are fever, cough and difficulty with breathing, medical attention should be sought immediately by calling by telephone first if possible, and following the directives of the local health authority 21.

It is essential to be up to date on the latest information from trusted sources, such as the WHO or local and national health authorities 21.

4.2. Best practices

Best practices are important, especially during this pandemic to pay attention to one’s health. According to the WHO, people who are vulnerable or at high-risk for COVID-19 are those who are older than 60 years or have health conditions such as lung or heart disease, diabetes or conditions that affect the immune system. The WHO provides information and advice on what to do and which actions to take to protect oneself 22.

It is one’s own responsibility to be aware about the safety of oneself and others. Not touching the products that we are not going to buy, washing fruits and vegetables before consumption, are common sense that we all must follow. Moreover, respecting quarantine and the recommended safety practices is strongly advised in order to minimize the risk for us but also for our communities.

A healthy and balanced diet as well as drinking a minimum of 1.5 liter of water per day are essential and even more so during this pandemic. In general, a healthy lifestyle is always of huge importance. Indeed, it is important to stay physically active, have sufficient sleep, reduce stress factors, limit exposure to blue light screens of computers, smartphones and other smart devices especially before sleeping, and practice relaxation techniques such as meditation.

4.3. Boosting the immune system

Nutrients such as magnesium, zinc and vitamins A, C, D and E may improve and support the immune system to fight diseases including COVID-19 28,29. Supplementation with vitamins A and D after influenza vaccination increased the humoral immunity of pediatric patients 29. Moreover, vitamin D has an effect that disrupts viral cellular infection by interacting with angiotensin converting enzymes (ACEs) 29. Some scientists studied the efficacy of vitamins in the prognosis of COVID-19, they mention that vitamins D and C could play important roles in determining the results of COVID-19 29-32.

With more people staying at home during the pandemic, some may have been deprived of vitamin D 33. The National health service of England recommends taking 10 micrograms of vitamin D a day if people are spending a lot of time indoors 33.

Associate Professor of dietetics and nutrition, Prof. Valencia Gisela at Florida International University recommends the top three supplements that adults should consider taking to boost their immune system and fight COVID-19 34:

– Vitamin C: 1,000 mg twice every day

– Vitamin D3: 1,000 International Units (IU) once or twice per day

– Zinc: 40 mg or less once a day

Nowadays many researchers and biotech companies are developing COVID-19 vaccines. Indeed, more than 200 COVID-19 vaccines are in development worldwide 35. These vaccines will teach the body’s immune system to safely recognize and block the COVID-19 virus 36. According to the WHO, there are 4 groups of vaccines 36:

– Inactivated or weakened virus vaccines, which use an inactivated or weakened form of the virus that it doesn’t cause disease but generates an immune response.

– Protein-based vaccines, which use harmless fragments of proteins or protein shells that mimic the COVID-19 virus to safely generate an immune response.

– Viral vector vaccines, which use a safe virus that cannot cause disease but serves as a platform to produce coronavirus proteins to generate an immune response.

– RNA and DNA vaccines, a cutting-edge approach that uses genetically engineered RNA or DNA to generate a protein that itself safely prompts an immune response.

On 31 December 2020, the WHO issued an Emergency Use Listing (EUL) for the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine 36. EULs followed for the AstraZeneca/Oxford university-developed vaccine, on 15 February 2021 36-37. More recently, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen developed a single dose vaccine which received an EUL on 12 March 2021 36-38. Until 13 April 2021, the recommended vaccines by the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen, while the AstraZeneca and Novavax COVID-19 vaccines are still in phase 3 clinical trials 38.

The WHO reported that by 10 May 2021, 1 206 243 409 vaccine doses had been administered 12. The WHO is actually on track to issue EULs for other vaccine products by June 2021 36. More mRNA vaccines are expected to be launched, in addition to many other vaccines that are in phase 3 large-scale clinical trials progress 39.

Since COVID-19 vaccines have only become available and in used in the past few months, it is too early to know how long they will provide protection or remain effective 36. Conventionally, vaccine development is a long and expensive process that and it usually takes many years to produce a licensed vaccine 40.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak is challenging the economic, medical, and public health infrastructure worldwide. The newly developed COVID-19 vaccines will not protect from future outbreaks of other zoonotic viruses and pathogens. Therefore, besides containing this outbreak, efforts should be made to develop comprehensive measures and preventive natural products to prevent future zoonotic outbreaks.

The WHO website can be accessed for regular updates on the COVID-19 pandemic: https://covid19.who.int/.

REFERENCES

1. Kannan, S., Ali, P. S. S., Sheeza, A. & Hemalatha, K. Covid‐19 (Novel Coronavirus 2019) – recent trends. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 2006–2011 (2020).

2. He, F., Deng, Y. & Li, W. Coronavirus disease 2019: What we know? J. Med. Virol. 92, 719–725 (2020).

3. Li, Q. et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1199–1207 (2020).

4. Chan, J. F. W. et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 395, 514–523 (2020).

5. Hageman, J. R. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Pediatr. Ann. 49, e99–e100 (2020).

6. Zumla, A., Chan, J. F. W., Azhar, E. I., Hui, D. S. C. & Yuen, K. Y. Coronaviruses-drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 327–347 (2016).

7. Singhal, T. Review on Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID19). Indian J. Pediatr. 87, 281–286 (2020).

8. Gretebeck, L. M. & Subbarao, K. Animal models for SARS and MERS coronaviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 13, 123–129 (2015).

9. Liu, C. et al. Research and Development on Therapeutic Agents and Vaccines for COVID-19 and Related Human Coronavirus Diseases. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 315–331 (2020).

10. Petropoulos, F. & Makridakis, S. Forecasting the novel coronavirus COVID-19. PLoS One 15, 1–8 (2020).

11. WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Data last updated: 2021/2/24, 10:20am CET (2021).

12. WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

13. Chowdhury, M. A. et al. Prospect of biobased antiviral face mask to limit the coronavirus outbreak. Environ. Res. 192, 110294 (2021).

14. European Medicines Agency, COVID-19 treatments: authorised. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/treatments-covid-19/covid-19-treatments-authorised. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

15. FDA. FDA’s approval of Veklury (remdesivir) for the treatment of COVID-19-The Science of Safety and Effectiveness. (2020). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fdas-approval-veklury-remdesivir-treatment-covid-19-science-safety-and-effectiveness. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

16. FDA. Know Your Treatment Options for COVID-19. (2021). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/know-your-treatment-options-covid-19. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

17. FDA. Emergency Use Authorization. (2021). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization#coviddrugs. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

18. Bansal, P. et al. Hydroxychloroquine: a comprehensive review and its controversial role in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann. Med. 53, 117–134 (2021).

19. Chen, N. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513 (2020).

20. Hui, L. et al. Can Chinese Medicine Be Used for Prevention of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A Review of Historical Classics, Research Evidence and Current Prevention Programs. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 11655, 1–8 (2019).

21. WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. World Health Organisation (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public. (Accessed: 19th April 2021)

22. WHO. World Health Organization. Available at: www.who.int. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

23. Singh, N. A., Kumar, P., Jyoti & Kumar, N. Spices and herbs: Potential antiviral preventives and immunity boosters during COVID-19. Phyther. Res. 1–13 (2021). doi:10.1002/ptr.7019

24. Kulyar, M. F. e. A. et al. Potential influence of Nagella sativa (Black cumin) in reinforcing immune system: A hope to decelerate the COVID-19 pandemic. Phytomedicine 153277 (2020). doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153277

25. Soni, Himesh, Sharma, S. & Malik, J. K. Role of Indian herbs against COVID-19: A Review. Sch. Int. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 3, 169–176 (2020).

26. Khanna, K. et al. Herbal immune-boosters: Substantial warriors of pandemic Covid-19 battle. Phytomedicine 153361 (2020). doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153361

27. Wang, W. Y., Xie, Y., Zhou, H. & Liu, L. Contribution of traditional Chinese medicine to the treatment of COVID-19. Phytomedicine 153279 (2020). doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153279

28. Arshad, M. S. et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and immunity booster green foods: A mini review. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 3971–3976 (2020).

29. Cimke, S. & Gurkan, D. Y. Determination of interest in vitamin use during COVID-19 pandemic using Google Trends data: Infodemiology study. Nutrition 85, 111138 (2021).

30. Rhodes, J. M., Subramanian, S., Laird, E. & Kenny, R. A. Editorial: low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51, 1434–1437 (2020).

31. Hemilä, H. & Chalker, E. Vitamin C as a Possible Therapy for COVID-19. Infect. Chemother. 52, 222–223 (2020).

32. Grant, W. B. et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and covid-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients 12, 1–19 (2020).

33. Roberts, M. Coronavirus: Should I start taking vitamin D? BBC news (2020). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/health-52371688. (Accessed: 19th April 2021)

34. Valencia, G. Three vitamins, minerals to boost your immune system and fight COVID-19. Florida international university (2020). Available at: https://news.fiu.edu/2020/three-vitamins,-minerals-to-boost-your-immune-system-to-fight-covid-19. (Accessed: 19th April 2021)

35. Dodd, R. H. et al. Concerns and motivations about COVID-19 vaccination. Lancet 21, 161–163 (2021).

36. WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Vaccines. (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-vaccines?adgroupsurvey (Accessed: 25th February 2021)

37. WHO. COVAX Announces new agreement, plans for first deliveries. (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-01-2021-covax-announces-new-agreement-plans-for-first-deliveries. (Accessed: 12th May 2021)

38. Different COVID-19 Vaccines Centers for disease control and prevention. (2021). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines.html. (Accessed: 13th April 2021)

39. WHO. Status of COVID-19 Vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process (16 February 2021). (2021). Available at: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/Status_COVID_VAX_20Jan2021_v2.pdf. (Accessed: 25th February 2021)

40. Lurie, N., Saville, M., Hatchet, R. & Halton, J. Developing Covid-19 Vaccines at Pandemic Speed. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1969–73 (2020).